Defusing the History Wars: Finding Common Ground in Teaching America’s National Story

Debates over Critical Race Theory. Combative school board meetings that have led to arrests. Bills that aim to impose limits on classroom conversations about racism and history. Today, America is embroiled in a culture war over whether we should see our national history as a source of pride or a source of shame.

We at More in Common are curious about these ‘history wars’— and through an extensive and in-depth exploration of American public opinion, we discovered they are often being fought between imaginary enemies.

To better understand this conflict, we conducted a year-long research project asking thousands of Americans their views of American history and national identity and what they understood to be the views of their fellow Americans.

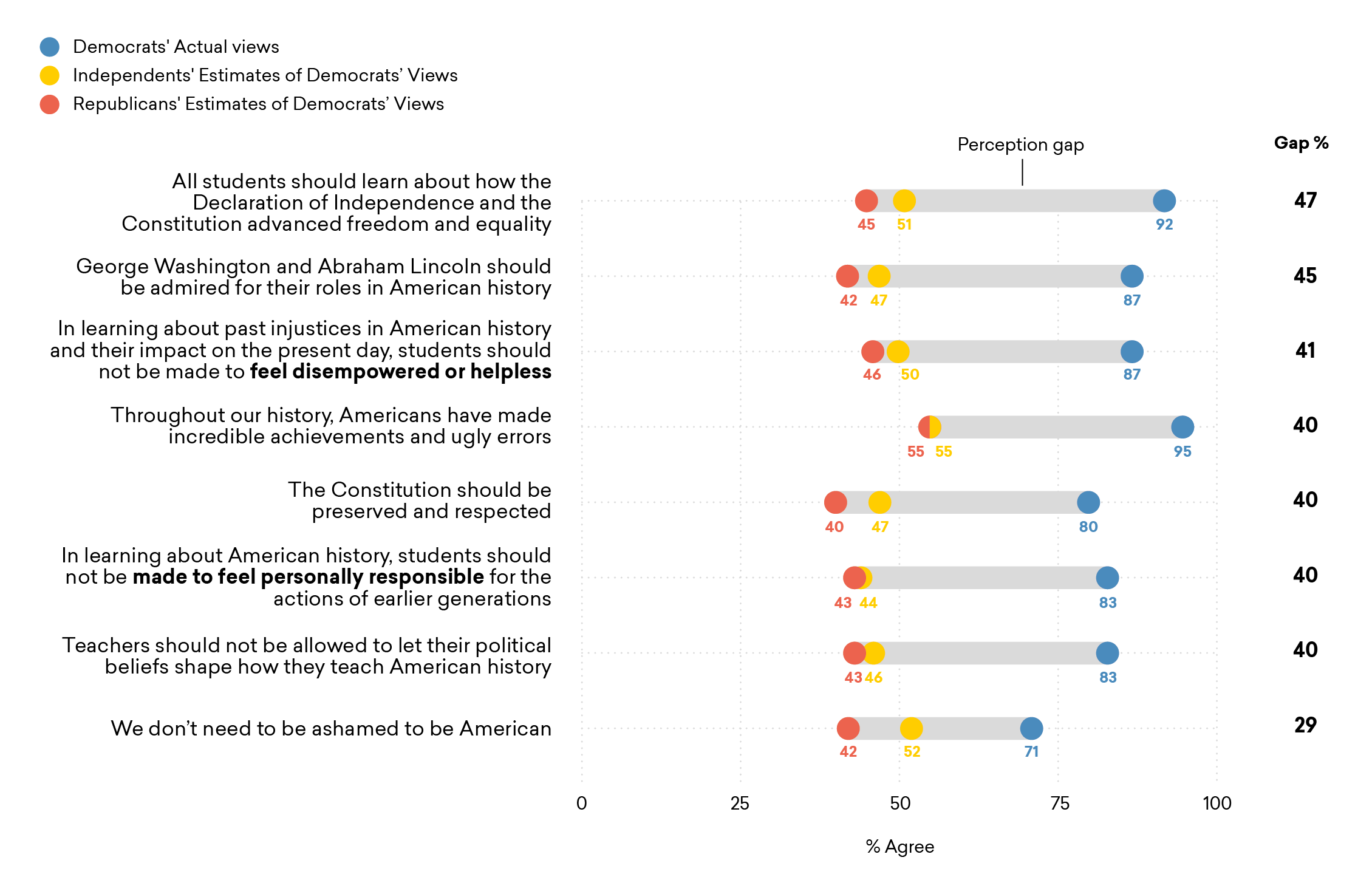

One of our most notable findings is that both Democrats and Republicans alike grossly overestimate whether members of the opposing party hold extreme views. We call this a ‘Perception Gap’ — the gap between what we imagine an opposing group believes and what that group actually believes.

Do you have a perception gap?

Take our quiz to find out how well you understand the views of people from the other party.

Many of our findings give reasons for hope. We found that a majority of Americans across political affiliations agree on fundamental ideas about our national history and how it should be taught.

However, when we focus only on the loudest voices, we fail to hear the most common perspectives.

False Divergence

Many Republicans believe most Democrats want to teach a history defined by shameful oppression and white guilt. Many Democrats believe most Republicans want to focus on the white majority and overlook slavery and racism. But we found that both impressions are wrong. These perception gaps between how each party perceives the other present a dangerous level of overstatement.

“I do think that the media or Republicans can think that the goal of learning all of American history or especially the negative parts is to make people, to make students, feel guilty or ashamed. Whereas I think in general, you know, the idea is more that we want students to just get a real understanding of what happened.”

—Michael, 35-44 white man, Democrat, Texas

For example, more than twice as many Democrats agree that all students should learn about how the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution advanced freedom and equality than Republicans think (92 percent versus 45 percent). Similarly, about twice as many Democrats believe students should not be made to feel guilty or personally responsible for the errors of prior generations than Republicans think (83 percent versus 43 percent).

Republicans Underestimate Democrats’ Commitment to Celebrating American Achievements and Overall Story of Progress

Question: [Democrats] Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? [Republicans/Independents] What percentage of Democrats do you think agree with the following statements? Source: More in Common

Democrats have large perception gaps when it comes to understanding how Republicans feel about teaching about failures in American history or about civil rights movements.

In a stark example, the proportion of Republicans who agree Americans have a responsibility to learn from our past is three times more than Democrats perceive it to be (93 percent versus 35 percent). Similarly, more than twice as many Republicans think schools should teach our shared national history as well as the history of specific groups such as Black, Hispanic and Native Americans than Democrats think Republicans believe (72 percent versus 30 percent).

“I would also want [Democrats] to know that I don't think I'm very different when it comes to teaching history than they are. I mean, I think we want to teach the facts. And we want to teach what happened. Even if that's a disturbing or dark past, I still think we should be teaching that. I think it's important so that we don't repeat that again.”

—Dan, 18-24 Hispanic man, Republican, Texas

Democrats Underestimate Republicans’ Willingness to Recognize Failures in American History and the Roles of Minority Groups in Making America Better

Question: [Republicans] Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? [Democrats/Independents] What percentage of Republicans do you think agree with the following statements? Source: More in Common

Points of Divergence

Our research found that the greatest disagreements are over two questions: first, how to draw connections between the past—especially past injustices—and present-day America and second, over the degree of emphasis currently given to the histories of minority groups.

While there is meaningful variation in responses to these questions by race, our data shows greater polarization by political ideology, as explained by More in Common’s Hidden Tribes typology.

For example, when asked whether America needs to do more to acknowledge past wrongs, white Americans are less likely than non-white Americans to agree: 51 percent of the white Americans we surveyed agreed with that statement, compared to 79 percent of Black Americans, 73 percent of Hispanic Americans, and 78 percent of Asian Americans.

But the disagreement is far greater between the extremist wing segments: A full 97 percent of Progressive Activists agree the country needs to do more to acknowledge earlier wrongs, whereas just 9 percent of Devoted Conservatives agree. The wings are similarly divided as to whether “Lingering on the past prevents us from moving forward.” A full 94 percent of Devoted Conservatives but only 11 percent of Progressive Activists agree with this statement.

Grappling with Our History: Views Vary More by Ideology than by Race

Source: More in Common

The other area of substantive disagreement is the extent to which specific groups’ histories are perceived to be prioritized in teaching history today.

For example, there is meaningful variation across racial groups on the question of whether specific minority groups are given preference relative to a history that elevates a shared national identity but the more extreme wing segments stand out for their contrasting views. Progressive Activists overwhelmingly disagree (94 percent) that the way Americans teach history prioritizes the stories of minority groups, whereas Devoted Conservatives uniformly agree (86 percent).

Telling Our Shared Story: Weaving the History of Particular Groups into History that Emphasizes a Common American Identity

Source: More in Common

Our research suggests that while there are genuine areas of substantive disagreement about how to teach American history, these debates are currently framed by segments holding the most extreme views, despite the fact that these two groups comprise only 14 percent of the U.S. adult population. This dynamic leads to situations in which communities spend time fighting imagined enemies instead of grappling with the substance where there is actual conflict.

Points of Convergence

Our research found important points of convergence in the debate on how to teach history. A clear majority of Americans wants American history to be taught in ways that include both the inspiring and the shameful and that allows students to learn from the past without feeling guilty or disempowered by the actions of prior generations.

“I think it's very important that students learn history, both the positives and the negatives, because this is where they live. And they have to understand where we came from as a country so that we don't repeat some of the same problems over and over again.”

Jake, 35-44 white man, Republican, Georgia

Strong Support among both Parties for Balanced Approaches to Teaching American History

Question: Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Note: Not every statement was asked of both political parties.

Source: More in Common

Our research also found that Americans converge more than they diverge over how to teach American history even on issues that are perceived as highly contentious, such as the history of racism. We found that 71 percent of Americans believe it is important to teach the history of racism and 80 percent of Americans believe it is important for students to learn about the history of Americans whose racial backgrounds differ from their own. Across many areas connected to matters of race and racism, such as teaching the history of slavery, Jim Crow, and segregation, we find strong levels of support across ideological lines.

“We shouldn't be ashamed to be American because we learn from the mistakes by writing laws to change the messed-up things that were once legal, from lynching, or segregation. We changed the laws, so we should be proud. So, we should admit our mistakes but…be proud that America fixed and changed the laws.”

Andy, 35-44 Black man, Democrat, New York

Substantive Support Across Parties on How to Teach about the Intersection of Race and American History

Question: Do you agree or disagree with the following statements? Note: Not every statement was asked of both political parties.

Source: More in Common

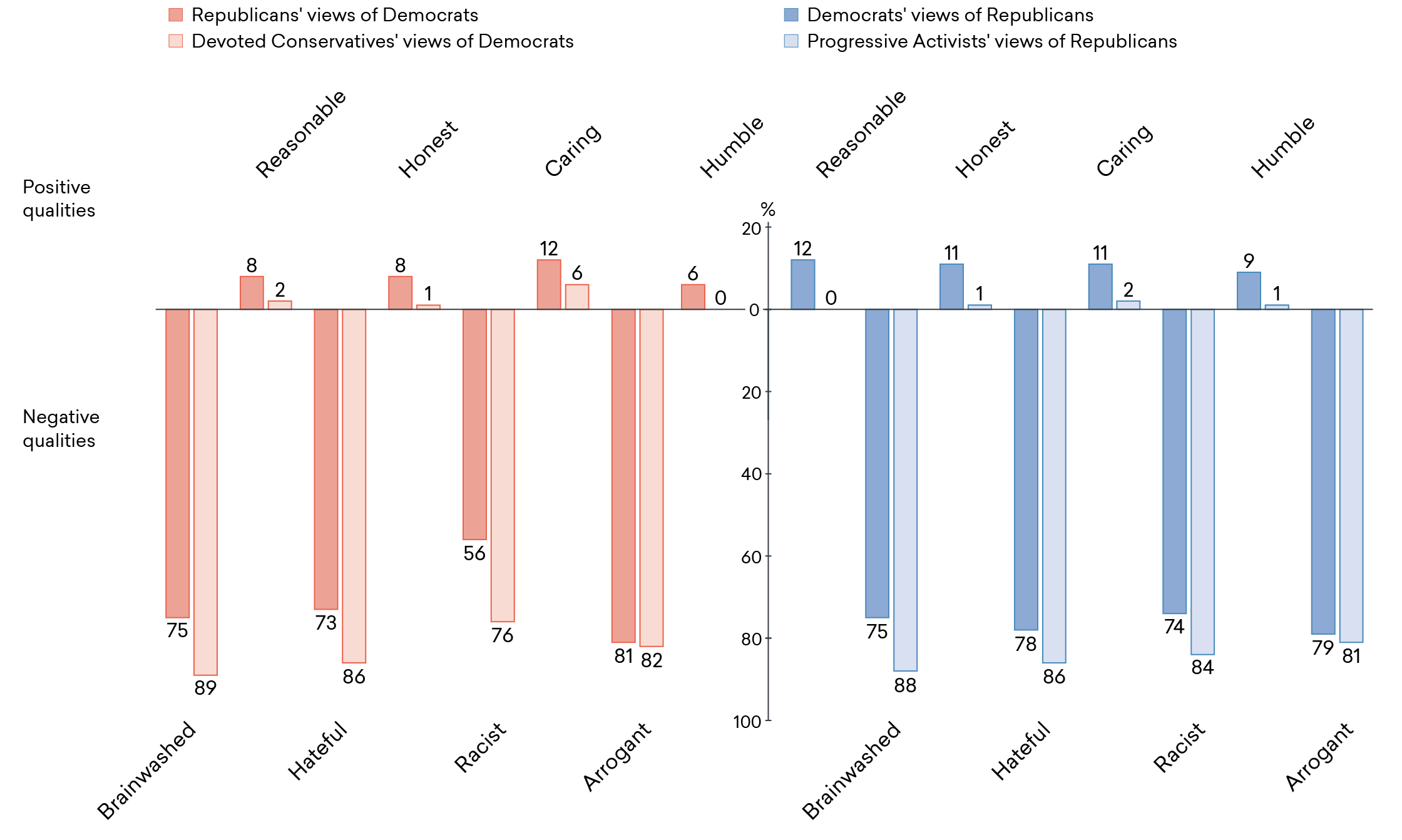

Polarization and Distrust

The history wars unfold at a time when Americans have a deep and pervasive sense that the country is divided and few institutions, including educational institutions, can be trusted.

This environment primes Americans to see imagined enemies and to believe the worst about their political opponents. In a striking example, our study found that more than 7 in 10 Democrats and Republicans perceive members of the other party to be “brainwashed,” “hateful” and “arrogant.”

Partisans Hold Deep Animosity Towards their Party Opponents

How much do each of the following phrases or words apply to Democratic / Republican voters?

Question: % indicating at least 5 on a 7-point agreement scale.

Source: More in Common

The distrust also affects schools. We found that about half—47 percent—of Americans say they do not trust education officials to be politically neutral in designing the curriculum, and only 41 percent of Americans think public schools are doing their best to teach American history in an accurate and unbiased way.

“I'm seeing on the news, where they're talking about Critical Race Theory, and teachers are pitting Blacks against whites—horrible stuff. But then my son comes home and I kind of want to pick his little brain to see what he's hearing. He's always like, ‘I don't know what you're talking about, we don't talk about that in school, my teachers never said that.’ And I've never witnessed anything like in assignments or homework that made me question what he's been taught. So I feel very conflicted. I don't know what to believe.”

—Tina, 45-54 white woman, Republican, South Carolina

Americans Have Low Trust that Public Schools Actually Teach an Honest Account of History

Most public schools in America are doing their best to teach American history accurately, without an agenda or bias

Question: Please state whether you agree or disagree with the following statements.

Source: More in Common

Recommendations

1.

Do not accept debates about teaching history framed in extreme binaries. Instead, assume greater complexity in the beliefs of Americans. Dispel the illusion of imaginary enemies by revealing the multitude of ways that Americans actually agree on how we should teach history.

2.

Cultivate more shared spaces for people to sensibly discuss and question these topics. Community institutions such as business groups, faith actors, veterans groups, and civil society organizations, should work together to create spaces that are intentionally designed to allow for more open and frank conversations, and that allow people to ask questions without fear of judgment.

3.

In communicating about how to teach history, use language that is concrete and accessible. Communication about how to teach history should be clear, specific and should refrain from jargon.

4.

Media should reject the presumption of conflict in the conversation about teaching history and when reporting, distinguish between areas of genuine disagreement and areas where Americans agree. Media should dedicate greater coverage to voices from the Exhausted Majority, who are likely to hold more nuanced views on issues of race, identity, and history.

5.

Organizations in the education space should build cross-cutting coalitions to push back against the highly toxic polarization of the history wars and set healthier norms for how communities address disagreements. Such networks can help establish and enforce boundaries to behavior and rhetoric that is considered acceptable—such as making clear that the community will not tolerate violence or dehumanizing rhetoric.

6.

Support and lead interventions to reduce perception gaps. An October 2022 study by Stanford University’s Strengthening Democracy Challenge has indicated that correcting such perceptions can reduce Americans’ support for partisan violence.

7.

Challenge zero-sum thinking. Americans should do more to lift up ways of teaching history where all groups feel their stories are included and where such learning reinforces a shared narrative of American history.

Conclusion

Given the enormity and complexity of our national story, teaching it has always been and likely will always be a subject of important and fraught debates. Our data shows that today we have much more overall agreement on how to teach history than we had in the past. But in a polarized political and media landscape, we currently do not see this common ground.

To bring Americans together in more constructive conversations about how to teach our history, leaders and communities at all levels need to take clear and decisive action. A key element in such efforts will be helping Americans envision what it could look like to have healthy and constructive conversations on how to teach history. It is easy to picture chaos and division, but what about unity and substantive debate?

After years of lowering our expectations of each other, this is a moment to imagine something brighter. We can start building this better future together with meaningful conversations about how to teach our past.

Read our Accompanying Black History Month Report

For Media Inquiries

michelle@moreincommon.com

Want to learn more?

Sign up here to get our newsletters and information.